Down to Pimlico again and round to Tate Britain, entering by the side entrance in Atterbury Street. The foyer here is a bit of a busy, messy space as visitors – especially newcomers to the place – tend to gather in little huddles in the middle while trying to orientate themselves and figure out which direction they should be headed for. Half a dozen paths converge here so there’s a choice of going off to the shop, the cloakroom, ticket desk, temporary exhibition space or up the stairs and on into the main, permanent collection. Consequently, it’s not really a very good place to try to display any artworks as there are just too many other things going on, all competing for the attention of the otherwise distracted artlover. Which is why, en route to the Queer British Art exhibition that I’ve come to take a look at today, I almost manage to walk past the David Medalla artwork that has been plonked down just by the exit doors leading out from that show.

Cloud Canyons No 3 is a sort of crazy kinetic sculpture consisting of a motorised electrical gizmo that mixes up soapy water into a bubbly froth and then slowly blows it out through a large plastic tube that’s been stuck vertically on the top. Originally constructed in 1961 (the one here is a recreation made in 2004) it’s a jokey, if somewhat dated, piece of art that nods to the world of Happenings and concerts featuring the likes of Pink Floyd and Soft Machine, and to a time when strobe lights flashed, joss sticks burned and lights projected through revolving gloops of oily coloured water created cosmic patterns that shone out onto the hordes of happy, hippies in attendance. If that antique music scene all seem terribly quaint and amateurish now, especially in comparison with the computerised technology involved in creating today’s stadium-sized lazer beam extravaganzas, back then it was considered to be extremely edgey and groovy, and the very essence of the ne plus ultra of trendy Modernist experimentalism. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, we now know that indulging in the act of blowing bubbles and puffing away on joints weren’t going to be the auguries ushering in the eagerly anticipated age of Aquarius, and that the world would soon turn its back on long hair, flared trousers, miniskirts and psychedelic colourfulness in general. Nevertheless, while it’s easy to mock the optimistic naivety that did once truly seem to sweep through great swathes of the Western world, especially amongst the younger generation, there really was something in the air that did eventually impact on the sensible sensibilities of the grow-ups who were meant to be in charge of running the place. Certainly, the old world order of automatic deference to the forces of the gray establishment did start to be questioned and challenged, and did finally result in the paradigmatic societal shift into what was then termed permissiveness – a term of opprobrium for some and approbation for others.

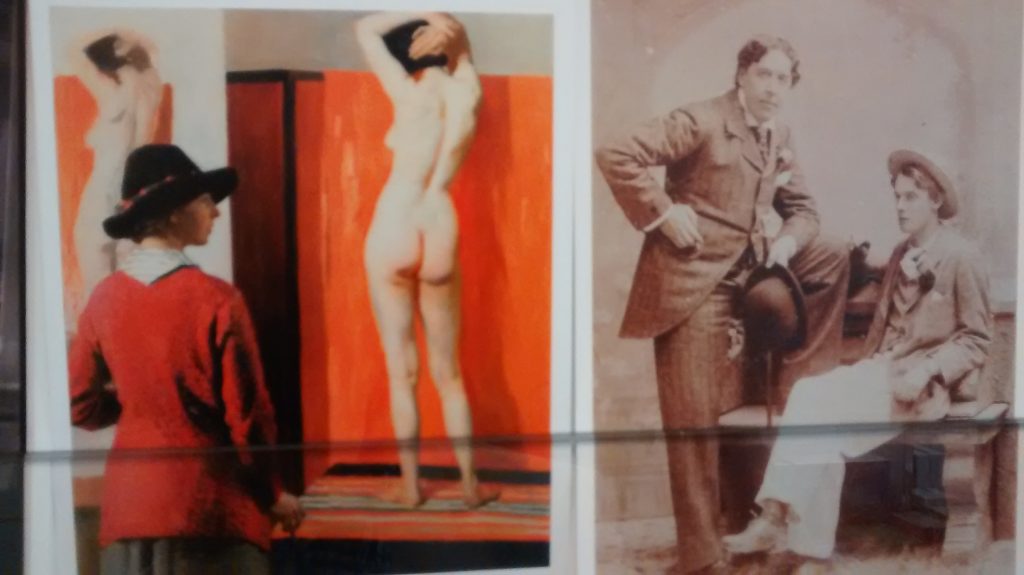

One of the undoubted milestones along this road to a more liberalised, less censorious and condemnatory, society came with the enactment of legislation in 1967 that began the decriminalisation of male homosexuality. And it’s a date that provides the cut off point for the works included in this current exhibition that aims to, ‘…explore connections between art and a wide range of sexualities and gender identities in a period of dynamic change’. So, the show starts off in the 1860s with some gay-ish scenes of Pre-Raphaelitism from Simeon Solomon and a bit of homoerotic beefcake courtesy of Lord Leighton’s sculpture of the Sluggard, a muscly, well-toned young man that seems to personify the louche lifestyle associated with the other great Victorian artistic movement of the time – the creed of Aestheticism. Of course, the most famous proselytiser of this deliberately amoral cultural tendency was Oscar Wilde and there’s a full length portrait of the author and playwright here, preening in his prime prior to his terrible fall from grace and subsequent incarceration in Reading Gaol. It seems that the curators have also managed to locate the actual bolted cell door behind which poor Wilde suffered his years in confinement, although I’m not sure as to why they then decided to put this particularly grim souvenir up on display. Then again, dotted throughout the exhibition is a curious range of other odd sorts of curios including Noel Coward’s red monogrammed dressing gown; a publicity shot of Danny La Rue complete with bouffant hairpiece and ball gown with saucy thigh-length slit; a batch of assorted wrestling magazines; and some of the actual library books to which Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell added their famously vulgar amendments.

Presumably these artefact are intended to add some kind of background chronological reference points to the exhibition but there’s a tendency towards the kitsch that maybe distracts a little from the rest of the more traditionally serious, straight-faced fine art on display elsewhere. Although, having said that, the curatorial aim of the exhibition seems to be sufficiently unfocused as to allow for just about anything to be included within this general visual sweep up of a century’s worth of Queer cultural collateral.

As for the rest of the art, I suppose it’s a bit of a ragbag mix of overwhelmingly figurative works comprising the odd landscape and still life but mainly portraits in one form or another by gay and lesbian artists of their various lovers, models and muses. Some of the imagery here makes the nature of the relationship between artist and subject very obvious – perhaps most explicit are the frankly pornographic line drawings by Keith Vaughan which, unsurprisingly, were never intended for public display. But while there are quite a few undisguised scenes of homoerotic suggestiveness – Duncan Grant’s large mural pool of lithe male swimmers; and its pendant here, Dame Ethel Walker’s frieze celebrating naked female pulchritude given cover by way of it classical title: The Excursion of Nausicaa – perhaps the majority of the artworks on display here look straight enough. At least they do to my inexpert eye.

And I suppose this again then rather begs the question as to what precisely is the point that the curators are trying to make with their very broad survey. Some works have clearly been included because of the sexuality of the artist who created them but then what does a straightforward but unexceptional flower study by Gluck tell us about her place on the LGBTQC spaghetti soup spectrum of sexual identities? And just because Laura Knight’s very stylish self-portrait shows her in the act of painting a nude female model, does that really confirm the artist’s Sapphic preferences. If that is indeed the case, then it was something of which I was previously unaware – not that I’m sure now how much difference it will make to me when I look at any of her works in the future.

The show ends with paintings from two of the most famous and respected of British artists, Francis Bacon and David Hockney. Such was the uncompromising nature of their individual personalities and such also was the changing nature of the times during which they worked that, unlike many of their predecessors in this show, neither seems to have been particularly inhibited in how they chose to live their own private-public lives. Did the fact that both artists were gay have any impact on their artistic modes of expression, on the compositions they created and the styles in which they chose to express them? Well, I suppose it’s yes, yes and yes again but as to what that means for members of the general public looking at any examples of their works, I think that that perhaps depends to a large extent on the eyes and interests of the individual beholders.

All in all, I suppose it’s not uninteresting to spend a while pondering the connections between art and the sexuality of those who make it, and occasionally to delve in the nether lands of the Queer fraternity and sorority to investigate how representations of aspects of their personal lives have been proffered with varying degrees of imagination, technical facility and candour. A thought I ponder as I exit the exhibition and, once again, encounter David Medalla’s mixed media sculpture as it continues to happily bubble away. Having now completed the Tate’s quick crash course introduction to Queer art history I feel that I should at least be ever so slightly more qualified to critique this example of the artist’s output. But then again looking at this foaming tube of frothy spume, I confess I feel utterly unmoved and wonder whether Freud had it right when he said that sometimes, after all, a cigar is just a cigar.